The Story of Chūshingura: Japan’s Timeless Tale of Loyalty and Honor

Among the many legends of Japan, few are as deeply loved and retold as Chūshingura, the story of the “Forty-seven Rōnin.” It is a tale of loyalty, revenge, and sacrifice that has captivated Japanese audiences for over three centuries. More than just a dramatic story, Chūshingura reflects the values of the samurai spirit—honor, duty, and loyalty to one’s master—and continues to influence Japanese culture today.

Historical Background

The true story behind Chūshingura took place during the early 18th century, in Japan’s Edo period (1603–1868). At that time, the country was ruled by the Tokugawa shogunate, a military government that maintained strict social order. Samurai served as loyal retainers to their feudal lords, or daimyō, and their code of ethics, known as bushidō (“the way of the warrior”), emphasized loyalty, courage, and self-discipline.

In 1701, Lord Asano Naganori, the young ruler of the Ako domain in western Japan, was called to Edo Castle (modern Tokyo) to perform official duties. There, he came into conflict with Kira Yoshinaka, a powerful shogunate official who was responsible for instructing the lords in court etiquette. Kira was said to be arrogant and corrupt, and when Asano refused to offer him bribes, Kira insulted and humiliated him repeatedly. Finally, unable to endure further abuse, Asano drew his sword inside Edo Castle and attacked Kira, slightly wounding him.

This was a grave offense—drawing a weapon inside the shogun’s castle was strictly forbidden. As a result, Lord Asano was ordered to commit seppuku (ritual suicide) on the very same day. His family lost their lands and titles, and his loyal samurai were left masterless—becoming rōnin, or wandering samurai. Kira, meanwhile, went unpunished.

The Revenge of the Forty-seven Rōnin

For most samurai, losing one’s master meant the end of one’s honor. However, Asano’s chief retainer, Ōishi Kuranosuke, could not accept this injustice. He gathered a group of 46 fellow rōnin who shared his loyalty, and together they swore an oath to avenge their lord’s death.

Knowing that the shogunate would be watching them closely, Ōishi devised a long and patient plan. The rōnin disbanded and went into hiding for almost two years, pretending to have abandoned their duty. Ōishi himself even took to drinking and frequenting the pleasure quarters of Kyoto, so that spies would believe he had given up on revenge. But in secret, he continued to plan the attack.

On a snowy night in December 1702, the rōnin struck. They surrounded Kira’s mansion in Edo and broke in. After a fierce battle, they found Kira hiding in a storage house. They offered him the chance to die honorably by seppuku, but when he refused, they beheaded him and brought his head to Sengaku-ji Temple, where their master Asano was buried. There, they laid the head before Asano’s grave and offered prayers for his spirit.

After the act, the 47 rōnin surrendered themselves to the authorities. Although the shogun admired their loyalty and bravery, they had still broken the law by committing murder. In 1703, all forty-seven were ordered to commit seppuku. Their graves can still be seen today at Sengaku-ji Temple in Tokyo, where many people come to pay their respects each year.

From History to Legend: The Creation of Chūshingura

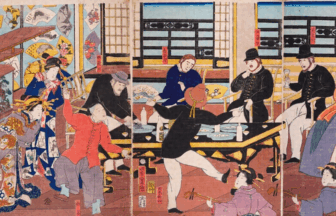

The historical incident soon became legendary. Because the Tokugawa government prohibited open discussion of the case (since it involved criticism of official authority), playwrights and storytellers disguised the names and settings. The most famous adaptation appeared in 1748 as a bunraku puppet play titled Kanadehon Chūshingura (“The Treasury of Loyal Retainers”).

In this version, the story is set in an earlier, fictional period, with the characters’ names changed—Asano becomes Enya Hangan, Kira becomes Kō no Moronao, and Ōishi becomes Ōboshi Yuranosuke. Despite these changes, the core of the story remained the same: loyal retainers avenging the unjust death of their master.

Chūshingura was later adapted for kabuki theater, and over time it became one of Japan’s most performed and beloved plays. It has been retold in countless forms—books, films, television dramas, and even modern manga and anime. Each generation continues to find new meaning in its themes of loyalty, justice, and personal sacrifice.

Cultural Significance

Chūshingura is much more than a revenge story—it is a reflection of the Japanese sense of morality and duty. The rōnin’s act of vengeance has long been debated: were they heroes who upheld justice and loyalty, or criminals who defied the law? This tension between personal honor and social order lies at the heart of the story’s power.

In the samurai code, loyalty to one’s master was considered the highest virtue, even above one’s own life. The 47 rōnin represent the ideal of chūgi (忠義)—absolute devotion and righteousness. Their willingness to die for their lord became a symbol of the pure samurai spirit, inspiring generations of Japanese to admire their courage.

The story also explores deep human emotions—grief, patience, perseverance, and moral conflict. Ōishi’s long wait and careful deception show not only strategic intelligence but also emotional endurance. The rōnin’s final act of suicide underscores the tragic beauty of bushidō: a life lived and ended with honor.

Modern Legacy

Today, the tale of the Forty-seven Rōnin remains deeply embedded in Japanese culture. Every year on December 14th, Sengaku-ji Temple hosts the Gishisai (Festival of the Loyal Retainers), where thousands of people gather to commemorate the rōnin’s sacrifice. Visitors from around the world come to see the graves, the armor and weapons used in the attack, and the scrolls of their final testament.

In popular culture, Chūshingura continues to inspire new interpretations. There are numerous film versions—ranging from faithful historical dramas to creative retellings such as Hollywood’s “47 Ronin” (2013), starring Keanu Reeves. Though many of these versions take artistic liberties, they all reflect the enduring fascination with the story’s themes of loyalty, justice, and redemption.

Why Chūshingura Matters

For many Japanese people, Chūshingura represents the soul of bushidō and the essence of traditional Japanese ethics. It raises universal questions: How far should one go to remain loyal? Is revenge ever justifiable? What is true honor? These questions continue to resonate not only in Japan but also with audiences around the world.

The rōnin’s story reminds us that loyalty and justice often come with personal sacrifice. It teaches the importance of perseverance, self-discipline, and moral conviction, even in the face of impossible odds. And though centuries have passed since the actual events, the emotions and values it portrays—loyalty, grief, honor, and courage—remain timeless and universal.

Visiting the Legacy

If you visit Tokyo, Sengaku-ji Temple in the Takanawa district is a meaningful place to experience the spirit of Chūshingura. The temple’s quiet graveyard contains the tombs of Lord Asano, Ōishi, and the 46 other rōnin. You can also see artifacts, letters, and weapons connected to the historical event. Each December, incense smoke fills the air as visitors pay their respects to the men who chose honor over life.

The site of the “Pine Corridor” (Matsu no Rōka), a long corridor that once stood within Edo Castle, is located in the East Gardens of the Imperial Palace.

Conclusion

Chūshingura is not merely an old story—it is a mirror reflecting Japan’s deep sense of loyalty, justice, and humanity. Through the bravery and devotion of the Forty-seven Rōnin, it continues to remind people of what it means to live with integrity and purpose. Whether seen as heroes or rebels, their legacy endures as one of Japan’s most powerful and moving tales.

How to Get to this place

Address:

1-3-28 Yokozuna, Sumida City, Tokyo

Access:

From Akihabara Station:

Take the Chūō-Sōbu Line(Local) to Ryogoku Station (about 5 minutes). Then walk about 7 minutes to the Honjo Matsuzakacho Park.

Places you can visit together:

Related tourist attractions:

No comments yet.