Ukiyo-e, literally meaning “pictures of the floating world,” is one of Japan’s most iconic forms of traditional art. It flourished during the Edo period (17th–19th century) and captured the vibrant life, beauty, and imagination of ordinary people living in that era. The term ukiyo originally meant “the transient world” — a reflection on the fleeting nature of human existence. But in Edo Japan, it came to represent the joyful, hedonistic urban culture that celebrated fashion, theater, travel, and pleasure.

In a time when Japan was closed to the outside world, the city of Edo (today’s Tokyo) was already one of the largest and most sophisticated cities on Earth, home to over one million people. Merchants and craftsmen prospered, and a unique urban culture bloomed. Ukiyo-e became a colorful mirror of that society — a form of mass entertainment and an art that reflected people’s dreams, passions, and everyday lives.

The Craftsmanship Behind Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e is a woodblock print — a result of the collaboration between three types of artisans: the designer (eshi), the carver (horishi), and the printer (surishi).

First, the designer draws the original picture on thin paper. The carver then meticulously engraves the lines onto a block of cherry wood. Finally, the printer applies pigments to the woodblock and presses it onto handmade Japanese paper (washi).

This process required extraordinary precision, teamwork, and artistic skill. Each color needed its own carved block, and the printer had to align them perfectly to create a clean, multi-colored image. By the mid-18th century, technological innovations made it possible to produce vivid multicolored prints, known as nishiki-e (“brocade pictures”). These dazzling works transformed Ukiyo-e into a truly popular art form, accessible to common people at affordable prices.

Subjects of Ukiyo-e: Beauty, Actors, Landscapes, and Stories

The subjects of Ukiyo-e are as diverse as the people who loved them. Artists captured not only the glamorous but also the ordinary — everything from courtesans to kabuki actors, from scenic landscapes to legends and daily life.

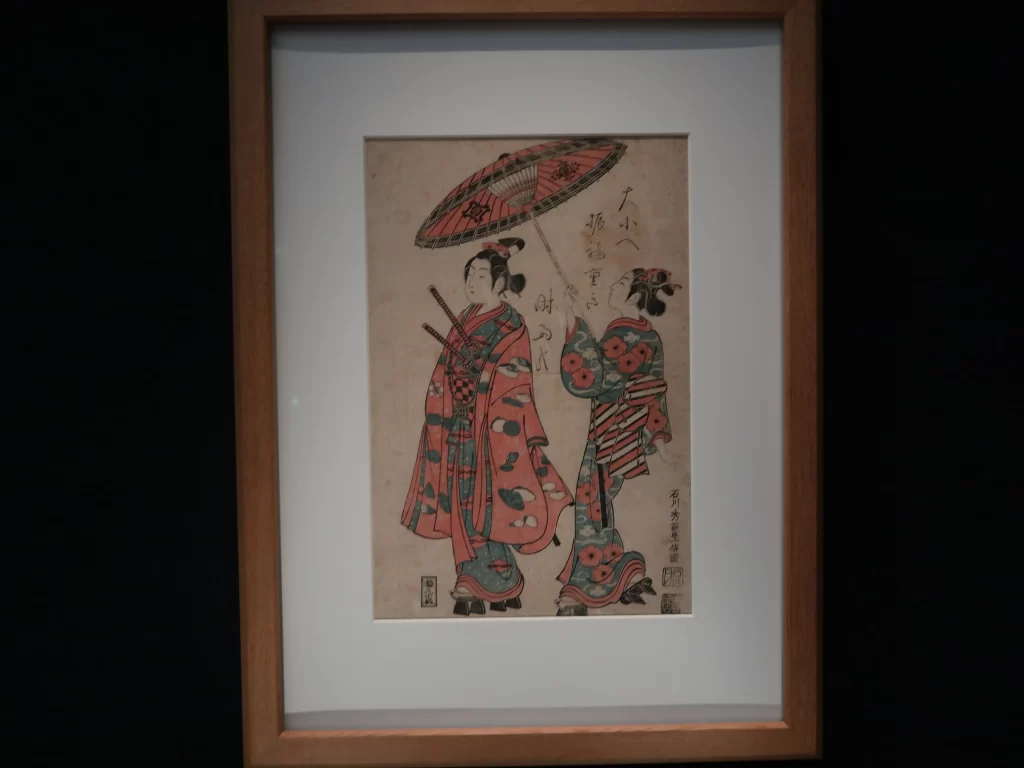

1. Bijin-ga (Pictures of Beautiful Women)

These prints depicted elegant courtesans and fashionable women of Edo, reflecting the trends of hairstyles, kimono patterns, and cosmetics. They were, in a sense, the “fashion magazines” of the Edo period. The artist Kitagawa Utamaro became famous for his sensitive portrayals of women’s expressions and emotions, elevating beauty itself into a poetic art form.

2. Yakusha-e (Actor Prints)

Kabuki was one of the most popular entertainments in Edo, and Ukiyo-e served as a visual record and promotion of its stars. Prints of famous actors in dramatic poses were the equivalent of movie posters or celebrity portraits today. Artists like Utagawa Toyokuni and Tōshūsai Sharaku skillfully captured the energy and charisma of the performers, preserving the excitement of the stage.

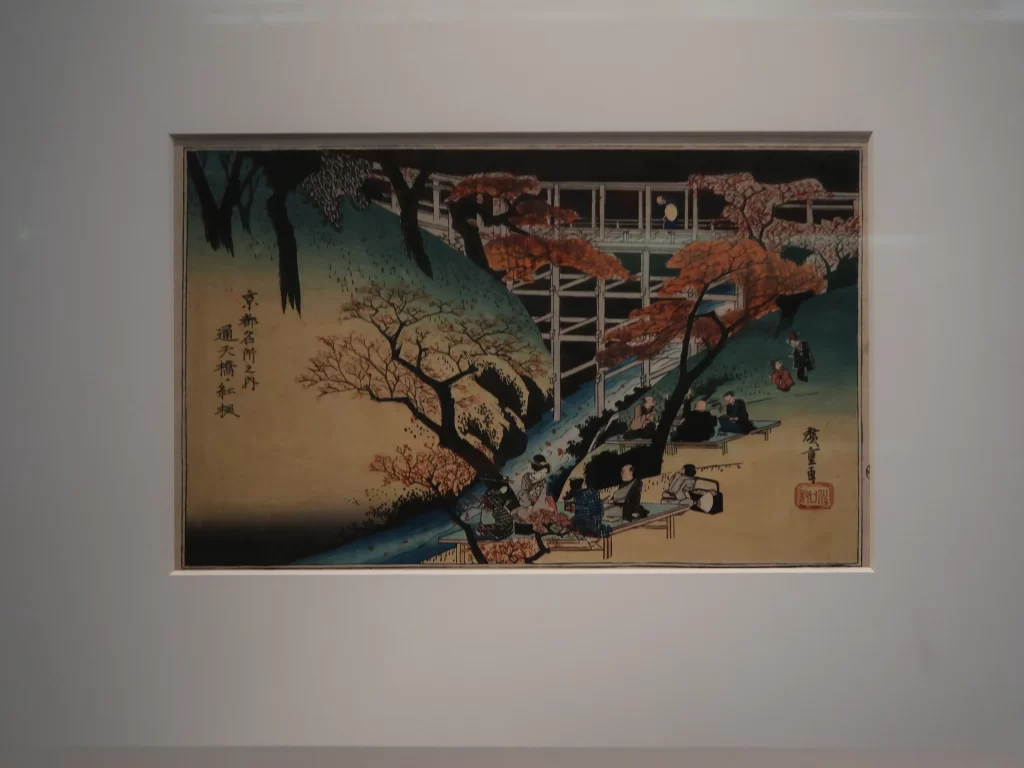

3. Fūkei-ga (Landscape Prints)

In the 19th century, landscape prints became a dominant genre. Artists began to look beyond the pleasure quarters of Edo to the natural beauty of Japan itself.

The most famous is Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), whose masterpiece series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji immortalized Japan’s sacred mountain in various seasons and moods. The best-known print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, with its enormous curling wave and tiny boats beneath Mount Fuji, is now one of the most recognized works of art in the world.

Another master, Utagawa Hiroshige, captured the poetry of travel and everyday life in his The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. His delicate colors and atmospheric scenes evoke the rhythm of a journey from Edo to Kyoto — from quiet rain showers to snowy villages. These works reveal not only Japan’s landscapes but also the sense of nostalgia and emotion that connects people to nature.

Ukiyo-e as Media — The “Pop Culture” of Edo

Ukiyo-e was more than art; it was also a form of mass media. In an age without photography, newspapers, or advertising posters, woodblock prints served as a powerful means of communication.

They reported on the latest kabuki plays, celebrity gossip, seasonal festivals, famous places, and even current events. Prints were affordable, easily distributed, and highly collectible.

In many ways, Ukiyo-e functioned like magazines, posters, or even social media today — spreading trends, sharing images, and shaping popular taste. People decorated their homes with them, exchanged them as gifts, and discussed them much like we share digital images today.

Ukiyo-e Crosses the Seas — The Birth of Japonisme

When Japan opened its ports to the West in the mid-19th century, Ukiyo-e prints began to flow overseas. At first, they were used as cheap wrapping paper for exports — but European artists and collectors quickly recognized their unique beauty.

This encounter sparked the movement known as Japonisme, the Western fascination with Japanese art and aesthetics. Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters such as Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Vincent van Gogh were deeply inspired by Ukiyo-e’s composition, flat color, and bold perspective.

Van Gogh famously copied Hiroshige’s prints and filled his paintings with the same strong outlines and vibrant contrasts. He once wrote to his brother Theo that Japanese art made him feel as if he were “in another world.” The influence of Ukiyo-e helped Western artists break away from traditional realism and explore new visual languages — changing the course of modern art.

Thus, Ukiyo-e was not only Japan’s art for its own people but also a bridge that connected Eastern and Western sensibilities.

The Legacy of Ukiyo-e Today

Today, Ukiyo-e remains one of Japan’s most celebrated art forms. Major museums around the world — including the British Museum in London, the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston — hold large Ukiyo-e collections. In Japan, exhibitions continue to attract visitors eager to experience the timeless beauty of these prints.

Moreover, the spirit of Ukiyo-e continues to inspire modern artists, designers, and filmmakers. Its influence can be seen in manga, animation, graphic design, and even fashion. The bold lines, dramatic perspectives, and storytelling of Ukiyo-e live on in contemporary Japanese visual culture.

Digital technology has also revived interest in the art form. Restorations, reproductions, and new interpretations are being made using digital tools, introducing Ukiyo-e to new generations around the world.

The Meaning of Ukiyo-e — Finding Beauty in Everyday Life

Ukiyo-e is more than a historical artifact; it is a window into the heart of Japanese culture. It expresses a way of seeing the world — finding beauty in daily life, joy in fleeting moments, and art in ordinary experiences.

The people of Edo lived in a world of impermanence, yet they celebrated life with humor, color, and imagination. Ukiyo-e captured that vibrant spirit. It reminds us that art is not only for the elite, but for everyone — that beauty can be found in the streets, in nature, and in the faces of people around us.

Even after three centuries, Ukiyo-e continues to speak across cultures and generations. Its message is universal:

Life is short, but beauty endures.

No comments yet.